NASA JSC

After finishing up graduate school, I hired on full-time in the Flight Mechanics and Trajectory Design Branch at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, where I had previously completed five internship/co-op rotations.

Artemis I Operations

I’ll be the first to admit I was lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time for this one. Artemis I, the first test flight of the SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft around the Moon, was set to launch shortly after I began full-time. Since I had previous experience with Artemis I off-nominal trajectory development, I was able to fast-track my certification as a Trajectory Analysis, Retargeting, and Optimization Officer (TARGO) in the Mission Evaluation Room (MER) in Mission Control Center (MCC).

I supported multiple shifts throughout the course of the 26-day mission (despite a brief hiatus after getting COVID while working console). Each shift, I’d communicate over the loops with other flight controllers, assess off-nominal trajectory capabilities for that phase of the mission, and update the current reference trajectory from navigation states received from the spacecraft. Not to mention, I got to be one of the first to see some of the incredible images downlinked from Orion during its two lunar flybys and coast in a Distant Retrograde Orbit (DRO) beyond the Moon. Overall, the mission was a wild success!

Artemis II Mission Design

Artemis II is the first crewed mission to the Moon since the Apollo missions in the 1970’s. The nominal trajectory spends about a day in High Earth Orbit (HEO) before injecting into a lunar free return trajectory, giving a total mission duration of about nine days. Off-nominal trajectory analysis is also a key area of concern for the mission design team, as continuous abort coverage throughout the entire mission is required to get the crew safely home under off-nominal events.

My task was to develop abort trajectories across a range of conditions, including different launch days, launch times, phases of the mission, times of abort burns, number of abort burns, engines used for burns, returns durations, and more. The sheer quantity of different permutations of abort trajectories (10,000+) meant that automation and parallel processing were critical. Individual trajectories would be numerically optimized with Copernicus, a generalized trajectory optimization software. Each of these individual trajectories would be represented as a single node in a giant Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) representing the entire scan. By developing the Python tools to automate the processing of this scan DAG, I was able to quantify our abort capability throughout the mission, a crucial step in developing flight rules for how the vehicle would be flown real-time.

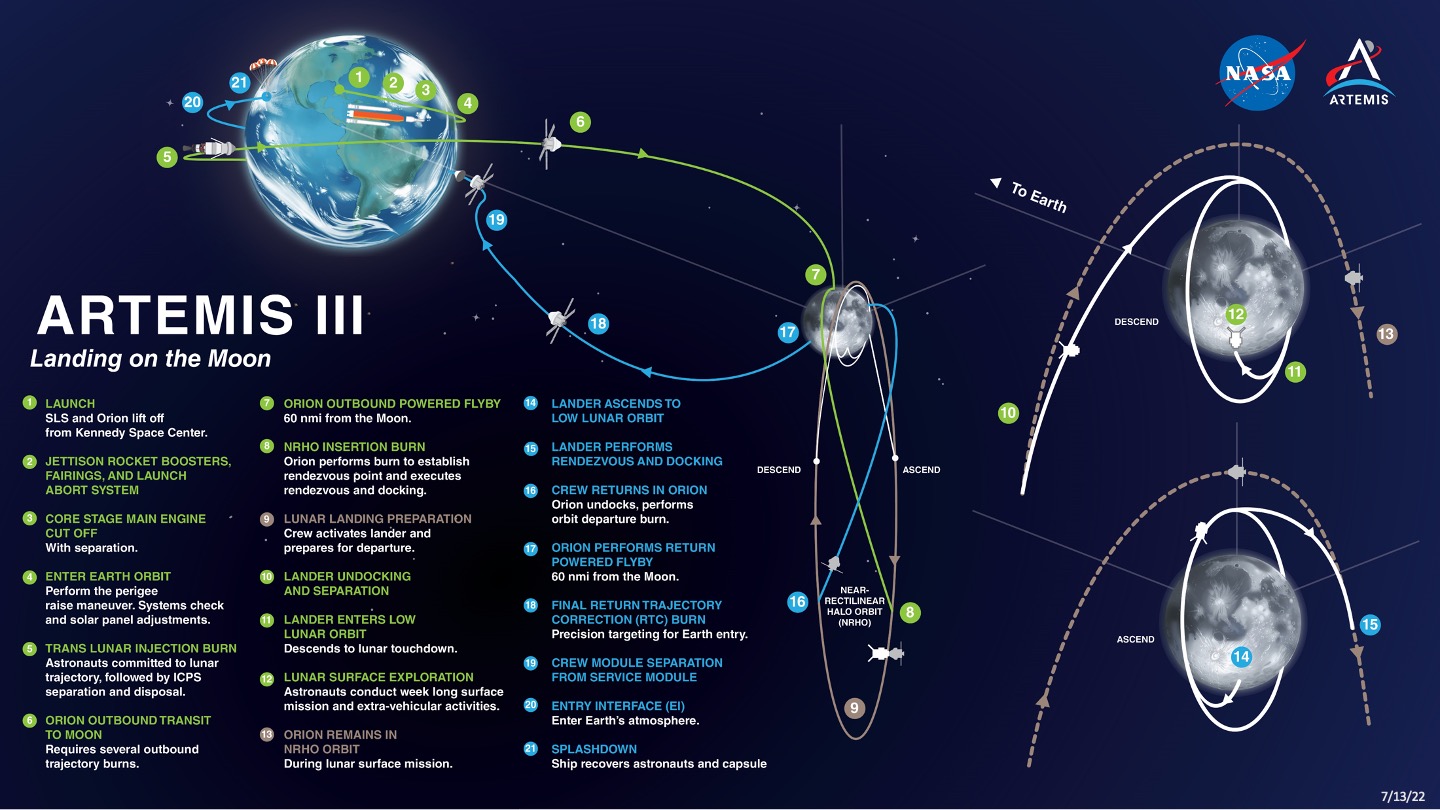

Artemis III+ Mission Design

Artemis III will be the first crewed mission to land humans on the Moon in over 50 years. The nominal trajectory is targeting a Near-Rectilinear Halo Orbit (NRHO), where Orion will coast before rendezvousing with the Human Landing System (HLS) vehicle to take the crew down to the lunar surface. Future Artemis missions (Artemis IV, Artemis V, etc.) will also follow similar mission profiles, targeting the NRHO as the baseline orbit.

Abort trajectory analysis is equally as imperative as for Artemis II. The difficult problem is this: how does one adapt the framework used for Artemis II aborts development to work for a completely different mission with a drastically different trajectory? This was one of our lessons learned from Artemis I - generalization of our tools is crucial for avoiding software rewrites each mission. Ultimately, I was able to generalize the aborts automation framework to be mission-agnostic, such that I could simultaneously churn out thousands of trajectories for Artemis II, Artemis III, and future missions. This allowed me to properly answer questions from key stakeholders on what amount of abort capability we would have during various phases of the mission.

Copernicus/LinCov (CopCov) Integration

This was a project/capability that my division had been interested in for a number of years. Copernicus is the trajectory design and optimization tool that our mission design teams use to develop in-space reference trajectories. LinCov is a linear covariance analysis tool that our Guidance, Navigation, & Control (GN&C) teams use to get statistical information for how well a given spacecraft’s GN&C system can actually follow the reference. These two tools historically had been developed completely separately from each other and operated independently by different teams. Robust trajectory optimization, whereby a trajectory is optimized with uncertainty (from an imperfect GN&C system) accounted for in the system, is possible if the two tools could interface more directly.

I developed an interface that allowed Copernicus to optimize trajectories while receiving trajectory dispersion data from LinCov in a direct feedback loop. Additionally, I was able to develop additional avenues for injecting dispersion data into the optimization algorithm. For example, a LinCov “Emulator” was developed that could use multivariate polynomial regression to fit large datasets of offline LinCov runs; this allowed Copernicus to optimize trajectories in a fraction of the runtime. I published a conference paper on my recent progress towards this integration effort at the AAS/AIAA Astrodynamics Specialist Conference in 2023.

Auto-Burn-Plan Management

This was a fun and exciting project for me to work on because it allowed me to dip my toes into a bit more of a project management role. Auto-Burn-Plan (ABP) was a tool that had been developed to act as a bridge between data products generated by our Mission Design teams and our GN&C teams. While ABP was hugely helpful in supporting the Artemis I mission as well as various tasks with our commercial partners, it was in need of a refactor for future Artemis missions. Though I inherited this code base early on in my full-time tenure, I was eager to learn its use cases as well as its deficiencies. I steered direction of this development effort to get us to a new, usable ABP 2.0 version that is now actively being used to support our future Artemis missions as well as NASA’s Human Landing System (HLS) commercial partners. I also interfaced with a variety of new teams and got a bigger picture understanding of how our various data products integrate into a larger flight readiness process.

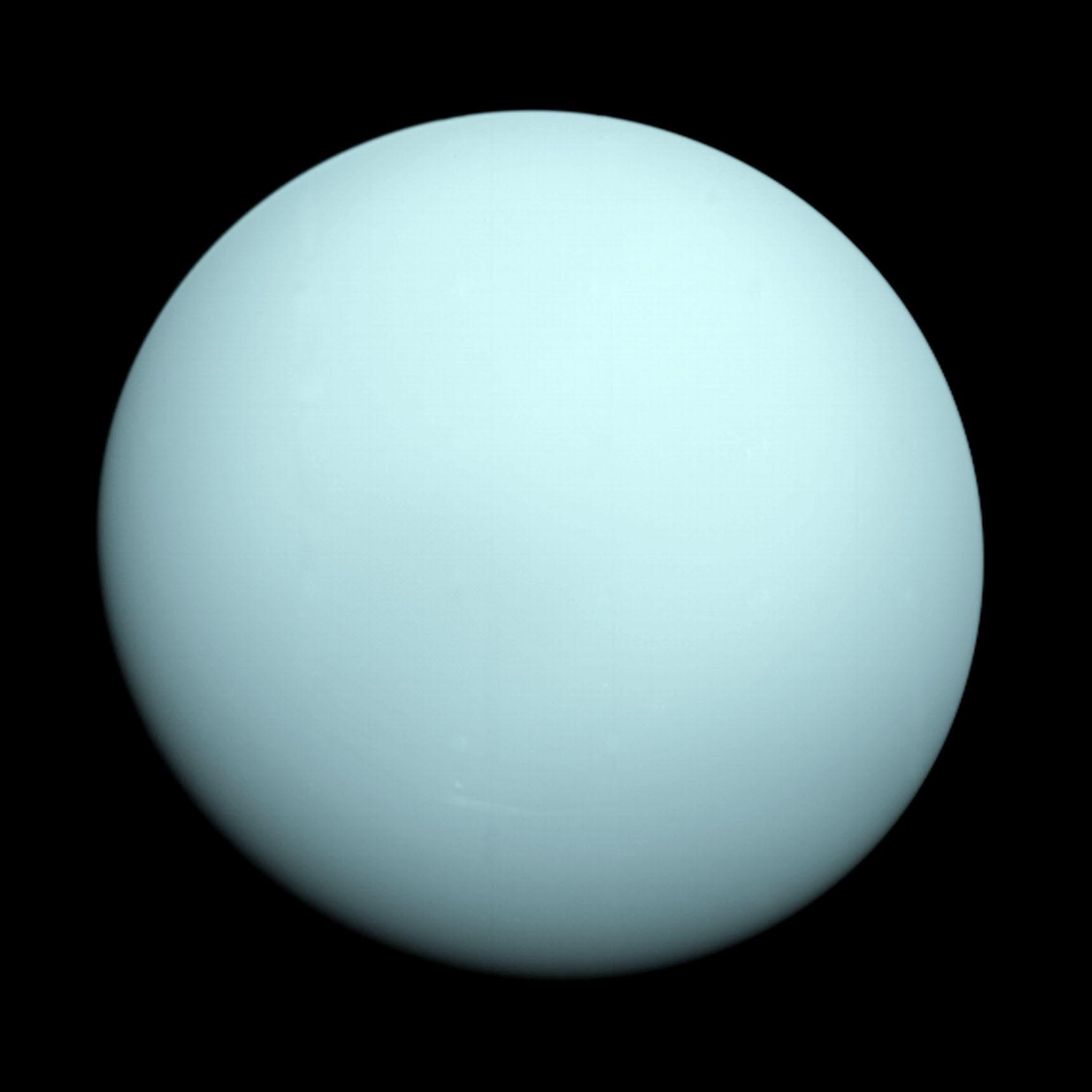

Ice Giants Aerocapture

Aerocapture is an intriguing idea - rather than performing a large maneuver to insert into a captured orbit around a planetary body, what if we instead dipped down into the atmosphere and used atmospheric drag to capture into orbit? While this maneuver has been researched for decades, it has yet to actually be demonstrated in-flight. However, recent advances in GN&C systems and thermal protection systems make aerocapture more feasible now than it’s ever been in the past. This project was to study the feasibility of using aerocapture to enable a flagship science mission to one of the Ice Giant planets - Uranus.

This was a cross NASA center, cross company, and cross discipline collaboration effort. On the JSC team, we are responsible for development, analysis, and integration of the guidance algorithm to be used during the aerocapture atmospheric pass. This included simulation development (using Julia programming language), Monte Carlo analyses, various tuning studies, and integration of the algorithm into the “runs-for-record” C simulations. As a part of this research effort, I also co-authored a conference paper for the 2024 SciTech conference.

Contractor Support

I’ve also worked on a couple of projects in collaboration with NASA’s industry partners. I have worked closely with teams at Blue Origin on cislunar trajectory design and robust trajectory optimization applications in support of a Space Act Agreement (SAA) to advance the technology readiness of their lunar landing system. More recently, I have also provided similar support as a part of their Human Landing System (HLS) contract to develop a human-rated lunar lander. Lastly, I am a Contracting Officer’s Representative (COR) supporting NASA’s partnership with Draper Laboratory.